Seeking evidence in herbal medicine

How to navigate influencers and science papers

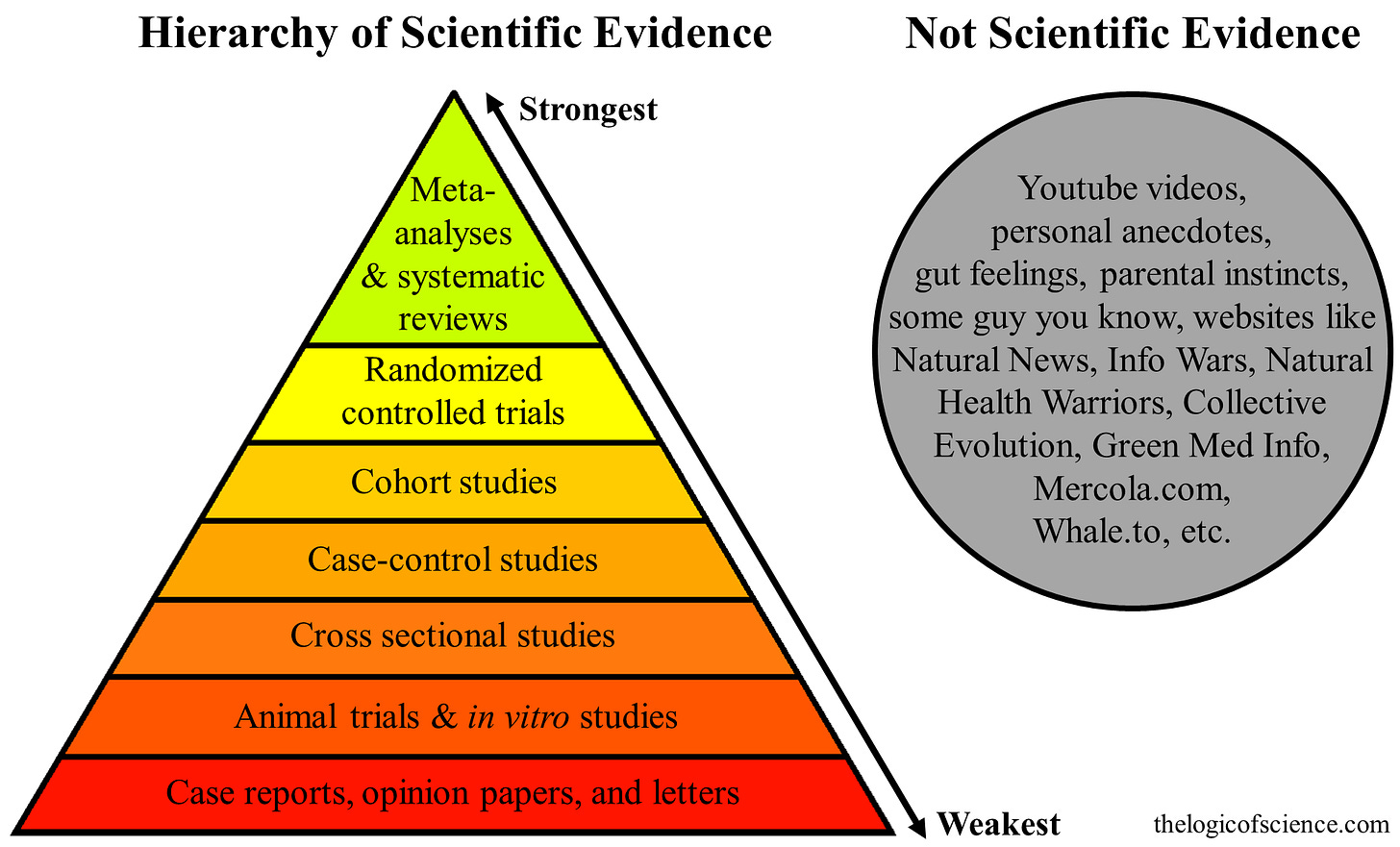

The concept of ‘hierarchy of evidence’ serves as a rough guide for evaluating research, but is just that: a guide. In the context of herbal medicine, which evolved through observation, tradition, and pattern recognition, applying this model too rigidly could flatten nuance. However, for clinicians and researchers working to bridge science and plant medicine, understanding where different forms of evidence fit and how to interpret them critically is essential.

The hierarchy of research evidence

At the upper end of this hierarchy are meta-analyses and systematic reviews. These studies generate new data by compiling and assessing existing research to uncover new patterns. Their strength lies in their breadth, but the accuracy of their conclusions depends entirely on the quality of the studies they include (Greenhalgh, 2023). One step below are randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which attempt to isolate a single variable – in this case, an herbal intervention – through strict experimental control. This structure is ideal for measuring clear outcomes in well-defined conditions (Bone & Mills, 2013), although it can feel disconnected from how herbs are used in practice, as these trials are not concerned with the whole plant itself.

Lower down on the scale are observational studies. These include designs that follow participants over time or compare groups based on lifestyle or exposure but do not manipulate the variables. They can highlight associations, offer real-world context, and generate meaningful questions, even if they cannot confirm causation. Case studies and experiential reports often sit at the base of the pyramid but can also be the starting point for innovation in clinical care.

Randomized control trials (RCTs) in herbal medicine evidence

In the realm of plant medicine, RCTs have become the go-to model for proving efficacy. They offer structure and the kind of statistical weight that regulators and journals expect. Applying this model to herbs, however, is complicated because botanical interventions are not single molecules. They are complex matrices of compounds that interact with each other and with human physiology in ways that defy simple cause-and-effect logic (Gagnier et al., 2006). RCTs frequently attempt to distill that complexity into one ‘active’ extract, delivered in a fixed dose, to a homogenous group of participants under highly controlled conditions. That structure, while rigorous, may underrepresent the way herbalists work with plants (Bone & Mills, 2013; Greenhalgh, 2023).

Several reviews have assessed the reliability of herbal randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A comprehensive analysis by Gagnier et al. (2006) revealed that many trials suffered from poor design execution. Critical elements, such as how the herbs were identified, the consistency of preparation, and the clarity of the control protocols, were often either vague or omitted altogether. Without these fundamentals, it becomes difficult to trust or replicate the outcomes. Similarly, Bloom et al. (2000) found that a significant number of studies evaluating herbal and complementary therapies lacked the methodological rigor expected in conventional biomedical research. These shortcomings weren’t necessarily due to weak interventions but rather to a misalignment between the research methods used and the realities of plant-based care.

That said, RCTs remain useful as they offer a degree of credibility and structure that is sometimes necessary for integration into broader healthcare frameworks. They are not the only legitimate form of evidence, however. Observational data, clinical experience, and long-standing traditional use all bring critical insights, especially in a field where variability is the rule, not the exception.

The conventional hierarchy of evidence offers a useful—but limited—framework for evaluating research in herbal medicine. While randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews provide structure and scientific legitimacy, they often fall short in capturing the dynamic, complex, and context-dependent nature of botanical interventions. Herbal medicine does not fit neatly into reductionist models; it is rooted in tradition, clinical observation, and real-world outcomes. Dismissing these forms of knowledge in favor of standardized trials risks oversimplifying the very systems we aim to understand. To advance the field responsibly, researchers and clinicians must embrace a more integrative view of evidence—one that values rigor without sacrificing relevance. By honoring both empirical science and lived experience, we can build a more holistic and practical evidence base for plant medicine.

References

Bloom, B. S., Retbi, A., Dahan, S., & Jonsson, E. (2000). Evaluation of randomized controlled trials on complementary and alternative medicine. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care, 16(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462300016123

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and practice of phytotherapy: Modern herbal medicine (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Gagnier, J. J., DeMelo, J., Boon, H., Rochon, P., & Bombardier, C. (2006). Quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials of herbal medicine interventions. The American Journal of Medicine, 119(9), 800.e1–800.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.006

Greenhalgh, T. (2023). How to read a paper: The basics of evidence-based medicine and healthcare (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

You are so correct in your paper on the problems of double blind studies and studies on herbal medicine and the flaws in that research. I have written articles in the past on this same subject. I deeply respect you on this.